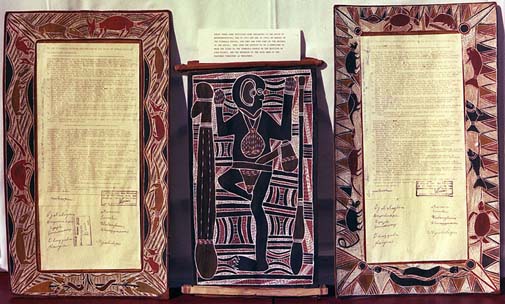

The tradition of bark painting at Yirrkala

Art, for the Yolngu, has long been a system of communication through which they have articulated their political structures, their spiritual inheritance and their unshakeable sense of being owners of the lands into which they are born. Through the forms and symbols of their paintings, and through the social practices by which the meanings of those paintings are told, withheld and exchanged in rituals of birth, death and initiation, Yolngu enact the enduring coherence of their society. Art is no mere past time for Yolngu, and it is more than beautiful decoration for its own sake. Yolngu art is one of the essential practices by which they reproduce themselves as a civilisation. It is integral to their politics, their education and their religion.

The Methodist missionaries who lived among Yolngu at Yirrkala from 1934 saw value in Yolngu art and so encouraged, for their own reasons, its continuing production. As brokers of paintings on bark to the outside world, the missionaries hoped to allow Yolngu a wholesome contact with the wider Australian economy and to encourage other Australians to respect Yolngu as human beings, rather than dismiss them as mere savages.

Howard Morphy, an anthropologist who has lived among Yolngu in order to appreciate the social significance of their art, has written that 'by the mid-1950s Yolngu had begun to appreciate the value of their art as a means of both asserting cultural identity and attempting to get Europeans to negotiate with them on their own terms. Yolngu organised ceremonies for departing missionaries, visiting politicians, and occasionally for anthropologists, that usually involved the gift of paintings and other objects of material culture. Such ceremonial presentations of gifts continue to the present.'

The 1963-bark petition was not the first time Yolngu had used their art to convey their senses of ownership and sovereignty to Europeans. In 1959, Yolngu had erected outside the church on Elcho Island a structure consisting of representations of sacred objects and collections of bark paintings belonging to many of the clans of the region. According to Morphy, 'they were among the clans most valuable property, objects of ritual power, and in Yolngu terms the most important things they had to give. The intention of the leaders...was not to reduce the power of the objects by releasing them from their shroud of secrecy but to assert to Europeans that Yolngu too had objects of great spiritual power and that they were willing to open these up to Europeans if Europeans were willing to reciprocate.'

The Methodist missionaries who lived among Yolngu at Yirrkala from 1934 saw value in Yolngu art and so encouraged, for their own reasons, its continuing production. As brokers of paintings on bark to the outside world, the missionaries hoped to allow Yolngu a wholesome contact with the wider Australian economy and to encourage other Australians to respect Yolngu as human beings, rather than dismiss them as mere savages.

Howard Morphy, an anthropologist who has lived among Yolngu in order to appreciate the social significance of their art, has written that 'by the mid-1950s Yolngu had begun to appreciate the value of their art as a means of both asserting cultural identity and attempting to get Europeans to negotiate with them on their own terms. Yolngu organised ceremonies for departing missionaries, visiting politicians, and occasionally for anthropologists, that usually involved the gift of paintings and other objects of material culture. Such ceremonial presentations of gifts continue to the present.'

The 1963-bark petition was not the first time Yolngu had used their art to convey their senses of ownership and sovereignty to Europeans. In 1959, Yolngu had erected outside the church on Elcho Island a structure consisting of representations of sacred objects and collections of bark paintings belonging to many of the clans of the region. According to Morphy, 'they were among the clans most valuable property, objects of ritual power, and in Yolngu terms the most important things they had to give. The intention of the leaders...was not to reduce the power of the objects by releasing them from their shroud of secrecy but to assert to Europeans that Yolngu too had objects of great spiritual power and that they were willing to open these up to Europeans if Europeans were willing to reciprocate.'

Keywords: activism, anthropology, Arnhem Land, bark petition, Blackburn, Justice, culture, Gove, Gove Case, Kakadu National Park, Marika, Roy, missionaries, missions, Northern Territory, Yirrkala, Yolgnu, Yunupingu, Galarrwuy

Morphy, Howard 1991, 'Ancestral connections: art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge', University of Chicago Press, pp 17,19. Still: Bark petition. Courtesy of AIATSIS.

Author: Rowse, Tim and Graham, Trevor

Author: Rowse, Tim and Graham, Trevor